February 19, 2019

The curious connections between Cordillera art and Filipino masters’ abstracts

Written by: Monchito Nocon

“It was over 25 years ago when I first came to the Philippines,” Swiss lawyer Martin Kurer tells me. “I was here to do some litigation and transaction related work,” he says rather demurely of how he ended up staying in the country.

We are in the middle of the exhibition space of 1335Mabini, the art gallery of Rudolf Kratochwill at the Karrivin Plaza in Makati, where an exhibition dubbed JUXTA:POSITION is being set up. For the show—“It’s non-commercial!” the owner emphasizes—an impressive collection of traditional Cordillera pieces will be on display alongside artworks by 20th and 21st century abstract artists.

“It started when I first visited a famous, local handicraft store,” Kurer recounts. “I was immediately attracted by a Maranaw drum.” From there, he moved on to Mindoro baskets, and then to art from the Cordillera peoples. And after meeting a well-known gallerist operating out of the heart of the City of Manila, he added paintings to his collection: Social Realist works at first, and eventually transitioning to abstract pieces.

“I was first in it for decorative purposes,” he admits.

This then leads us to JUXTA:POSITION, and the rationale behind juxtaposing bulols, boxes, and bowls with master works by Lee Aguinaldo, Cesar Legaspi, Arturo Luz, Fernando Zobel, Lao Lianben and Gus Albor.

“As a collector, I remain fascinated by the fact that artists from different continents, very distinct cultural heritages, and from very different epochs, could end up employing, or be perceived to be employing, very similar aesthetic approaches,” Kurer writes in the introduction to the three-part book, also of the same title as the exhibit.

To put things into better perspective, there’s his diptych by Jose Joya, circa 1964, called Controversial Composition #21—a still-life rendered in abstract—which is juxtaposed with a bowl (kinahu), Ifugao, from Northern Luzon, Philippines, from the early 20th Century. The circular abstract images that populate Joya’s canvas—blurred, faded—is almost akin to the Ifugao bowl, largely circular and resembling seemingly a tortoise.

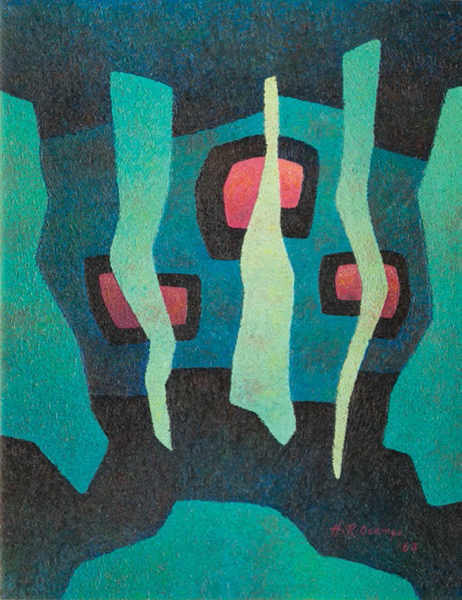

And then too, there’s his Hot and Cold (Set of 2) by Hernando R. Ocampo, circa 1963 that is juxtaposed with a bulul pair, Ifugao, Northern Luzon, Philippines, from the Late 19th Century. Ocampo’s two canvases, with their towering, vertical “space age” abstractions, can easily stand beside Kurer’s bulul pair—standing erect—without feeling, well, out of place.

And then too, there’s his Hot and Cold (Set of 2) by Hernando R. Ocampo, circa 1963 that is juxtaposed with a bulul pair, Ifugao, Northern Luzon, Philippines, from the Late 19th Century. Ocampo’s two canvases, with their towering, vertical “space age” abstractions, can easily stand beside Kurer’s bulul pair—standing erect—without feeling, well, out of place.

Kurer is also quick and honest enough to say that he is not a scholar—does not have the necessary educational background to delve into aesthetic and artistic principles—but rather tries to find some aesthetic interaction among the artworks in his collection. The late dealer and antiquarian Ramon Villegas also encouraged him to “look at art in a holistic manner, to try and understand the pieces from different ages and backgrounds.”

For Kratochwill’s part, who has been a gallerist and a tribal art dealer for close to four decades now and is an old friend of Kurer, he says that exhibits of this nature are already commonplace abroad. He mentions one happening at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1988, and at the Fondation Beyeler in Riechen in 2009. “Here in the Philippines,” he says, “this is likely the first time this is happening.”